12 Feb2021

share

To read the original article in TIME By Kharunya Paramaguru click here

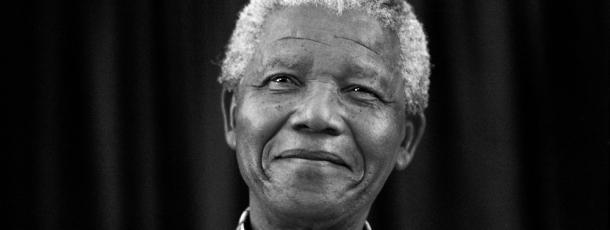

Following the news of the passing of Nelson Mandela at the age of 95, millions of people in South Africa and around the world have been in mourning. His image, writes Rick Stengel, TIME’s former managing editor and collaborator with Mandela on Mandela’s 1993 autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, “has become a kind of fairy tale: he is the last noble man, a figure of heroic achievement.” The many tributes pouring in from world leaders are testament to those achievements. But it is the memories shared over the years by some of the people who knew him and those who only had brief encounters that best illustrate the kind of man Mandela was.

ANC’s, South Africa’s governing political party, Deputy Secretary-General Jessie Duarte, who was his personal assistant between 1990-94:

“He always made his own bed, no matter where we traveled. I remember we were in Shanghai, in a very fancy hotel, and the Chinese hospitality requires that the person who cleans your room and provides you with your food, does exactly that. If you do it for yourself, it could even be regarded as an insult.

So in Shanghai I tried to say to him, ‘Please don’t make your own bed, because there’s this custom here.’ And he said, ‘Call them, bring them to me.’

So I did. I asked the hotel manager to bring the ladies who would be cleaning the room, so that he could explain why he himself has to make his own bed, and that they not feel insulted. He didn’t ever want to hurt people’s feelings. He never really cared about what great big people think of him, but he did care about what small people thought of him.”

South African photographer, Steve Bloom, whose father, Harry Bloom was a political activist:

During the 1950s my parents, who were anti-apartheid activists, knew Nelson Mandela. I remember the story he told them about the occasion he saw a white woman standing next to her broken car in Johannesburg. He approached her and offered to help. After fiddling with the engine he fixed the car. Thankful for his help, she offered to pay him sixpence.

“Oh no, that’s not necessary,” he said, “I am only too happy to help.”

“But why else would you, a black man, have done that if you did not want money?” she asked quizzically.

“Because you were stranded at the side of the road,” he replied.

Neville Alexander, a political activist who spent ten years imprisoned on Robben Island alongside Mandela, describes his first meeting with him:

“I was impressed mainly by the warmth and the genuine interest, which was a feature that, subsequently I discovered, is very much part of the man and something which I also must admit now, I learned from him … to give your full attention to your interlocutor, and really take notice of what people are saying, listen to them carefully. In his case, there was a spontaneous, charismatic exuding of warmth. That’s probably the most important, most vivid memory I have of our first meeting.”

Wolfie Kodesh, who hid Mandela for nearly eight weeks in 1961 in his apartment in a white suburb of Johannesburg:

“…We had a discussion and an argument about who is going to sleep where. I had a tiny flat … and I had a bed and I had a camp stretcher in a cupboard. So when I brought out the camp stretcher, I said to him, ‘Well, I’ll sleep on the camp stretcher. You sleep on the bed because you are six foot something, I am five foot something. So the stretcher is just right for me.’ No, he wasn’t going to have that. He hadn’t come there to put me out, and we had a bit of a talk about that and … it was arranged, and I would sleep on the bed.”

Rick Stengel, who spent almost two years with Mandela working on his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom:

“In 1994, during the presidential-election campaign, Mandela got on a tiny propeller plane to fly down to the killing fields of Natal and give a speech to his Zulu supporters. I agreed to meet him at the airport, where we would continue our work after his speech. When the plane was 20 minutes from landing, one of its engines failed. Some on the plane began to panic. The only thing that calmed them was looking at Mandela, who quietly read his newspaper as if he were a commuter on his morning train to the office. The airport prepared for an emergency landing, and the pilot managed to land the plane safely. When Mandela and I got in the backseat of his bulletproof BMW that would take us to the rally, he turned to me and said, “Man, I was terrified up there!”